Your next case coming to the practice is a small breed dog with a history of progressive pelvic limb lameness. The top differentials for this presentation are patellar luxation and cranial cruciate ligament disease.

But what about the patient with concurrent patellar luxation and cranial cruciate ligament disease? How do we reach a diagnosis of this challenging combination of diseases and how do we return the patient back to function?

Up to 25% of patients with patellar luxation are affected by concurrent cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) disease(Campbell, 2010). Older patients and those individuals with a higher degree of luxation were more likely to be affected by CCL disease. When faced with the challenge of a dog with a low grade chronic MPL (medial patellar luxation) and an acute clinical deterioration, evaluation for the presence of concurrent cranial cruciate ligament can help identify the true cause of deterioration in the patient’s lameness.

For patients with partial CCL disease, clinical presentation varies from mild to moderate weight-bearing lameness that worsens after strenuous exercise with stiffness commonly seen after rest. Meniscal injuries and complete rupture of the CCL can lead to acute deterioration. Dogs with patellar luxation can present varying levels of disability ranging from skipping lameness to inability to jump.

Differentiating between MPL, and MPL with concurrent CCL disease, is challenging. You must evaluate the patella and stifle stability separately. The stability of the patella should be evaluated during flexion and extension as well as during internal and external rotation of the tibia. Patients with concurrent CCL tend to have a stifle effusion with palpable fibrosis on the medial aspect of the stifle for more chronic cases (medial buttress). CCL disease is confirmed during physical examination by demonstration of instability during the cranial drawer manoeuvre and tibial compression test.

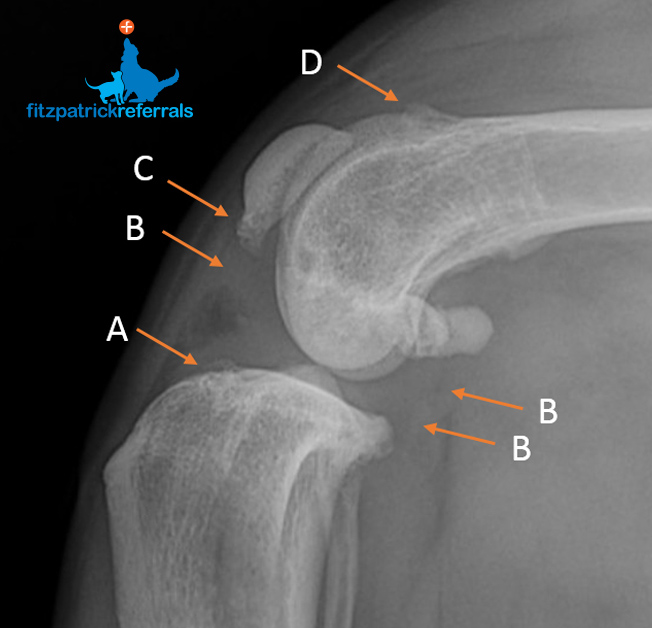

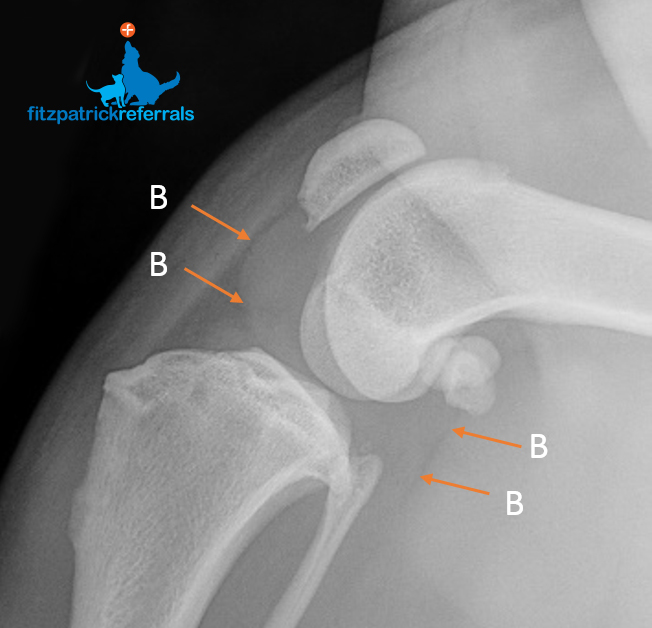

The classical radiographic presentation in patients with MPL and CCL are demonstrated in the radiographs in this article. A full pelvic limb radiographic evaluation, including ventro-dorsal extended hips and orthogonal views of the stifles, is recommended before making any surgical decisions. The complexity of MPL and concurrent CCL disease means treatment must be tailored to the individual taking into account patient size, skeletal conformation and grade of patellar luxation.

We focus initially on stabilising the stifle; usually utilising a variation of tibial plateau levelling osteotomy (TPLO), followed by stabilisation of the patella using a combination of patellar mechanism realignment and sulcoplasty. In some cases, we may have to carry out both tibial and femoral osteotomy to achieve stifle and patellar stability.

1 comment

At what age is a dog no longer a viable candidate for this type of surgery? Can I keep him comfortable with pain meds and supplements instead of surgery?